Pathogenesis

The lungs are constantly exposed to pathogens through aspiration; however, the lower airways usually remain sterile related to innate and acquired immunity of the pulmonary system (Marrie, 2013). Pneumonia can develop after aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions, inhalation of causative microorganisms, or when bacteria from an infection elsewhere in the body spreads to the lungs (ex. Bacteremia caused by IV drug use). If pathogens are able to move past the first line of defense in the upper airway (i.e. cough reflex, mucociliary clearance) to the lower respiratory tract, development of pneumonia depends of virulence of the microorganism and the host's defenses (McCance & Heuther, 2010).

Factors that can increase the host's risk for infection include:

- Advanced age

- Immunocompromise (ex: HIV/AIDS, chemo)

- Underlying lung disease (ex: COPD, cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis)

- Smoking history

- Alcohol consumption

- Altered LOC

- Impaired swallowing and entotracheal intubation

- Immobilization

- Cardiac and/or liver disease

- Malnutrition

- Medications that decrease gastric pH (ex: H2 receptor blockers)

(Marrie, 2013; McCance & Heuther, 2010)

Pathophysiology

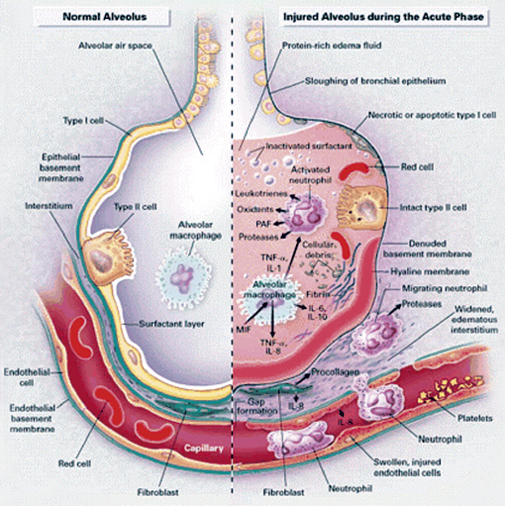

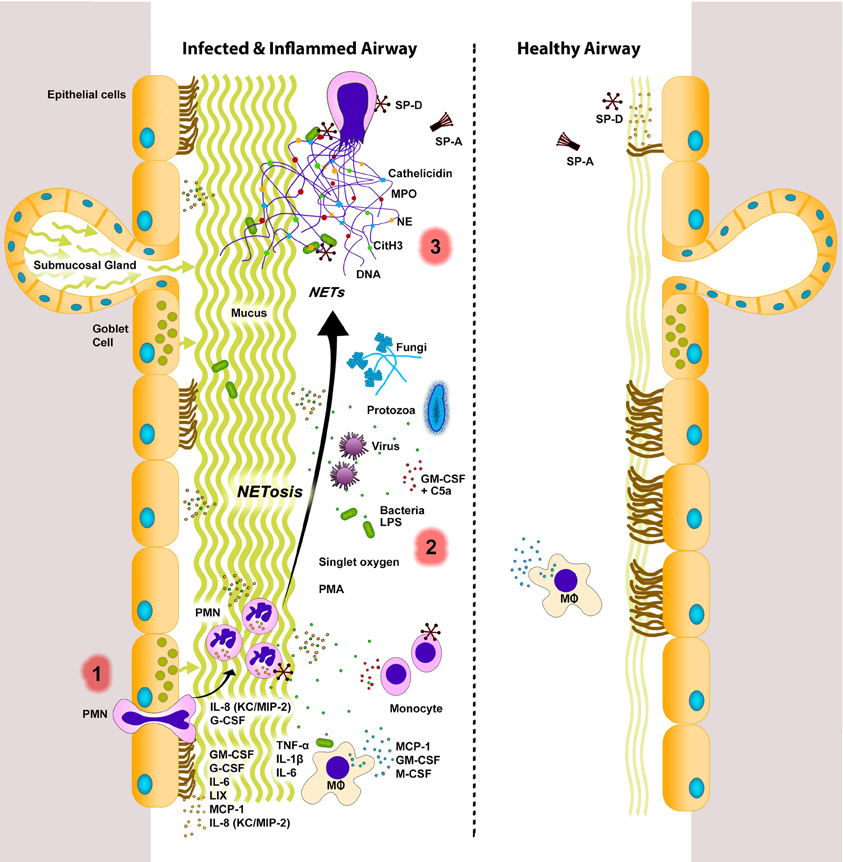

CAP is most commonly caused by aspiration or inhalation of microorganisms through the nasopharynx or oropharynx. Microorganisms are usually trapped in the mucous-producing cells and cilia that line the upper airway. Factors that can impair the lungs' first line of defense include suppressed cough reflex, decreased ciliary action, decreased activity of phagocytic cells, and the accumulation of secretions. If the microorganism gets past the upper airways line of defense, the next line of defense is the airway epithelial cells which contain alveolar macrophages. Alveolar macrophages release cytokines and cause widespread inflammation in the lungs in an attempt to activate the immune response. The products of inflammation (inflammatory mediators, immune complexes) can damage the lung tissue and cause the terminal bronchioles to fill with infectious debris and exudates. Some microorganisms also release toxins which can cause further damage to the alveolar walls. Accumulation of exudates can leads to alveolar edema resulting in dyspnea and hypoxemia (McCance & Heuther, 2013, Miskovich-Riddle & Keresztes, 2006).

Typical bacteria will usually cause lobar pneumonia which is characterized by consolidation in a portion of the entirety of one lung (Miskovich-Riddle & Keresztes, 2006 ). In lobar pneumonia, biproducts of inflammation such as cytokines damage the fragile alveoli and cause edema. This edema becomes are good medium for further bacterial proliferation and colonization. The inflammatory response results in solidification of the lung tissue as it fills with exudate of blood, fibrin, bacteria, etc. causing a reddened appearance of the lungs. This is called red hepatization. Red hepatization eventually progresses to gray hepatization; the lung tissue turns gray from fibrin deposition and phagocytosis by neutrophils of the inflammatory biproducts and microorganisms. Resolution follows when neutrophils are replaced by macrophages, eventually eliminating the infection (McCance & Heuther, 2010).

Atypical pathogens generally cause bronchopneumonia or interstitial infiltrate characterized by patchy inflammation and edema of both lungs (Miskovich-Riddle & Keresztes, 2006).